Submitted by Jane Kretzmann, on behalf of Elders for Infants (Glenace Edwall, Dave Ellis, Sandy Heidemann, Jim Nicholie, Glen Palm, and Katie Williams).

Elders for Infants is comprised of professionals who have worked in Minnesota in fields of child care, public health, parent education, academia, philanthropy, and government over the past 40 years. Using this knowledge and experience, we offer reflections and questions regarding the Office of the Legislative Auditor’s (OLA) Evaluation of Early Childhood Programs. These programs also span 40 years.

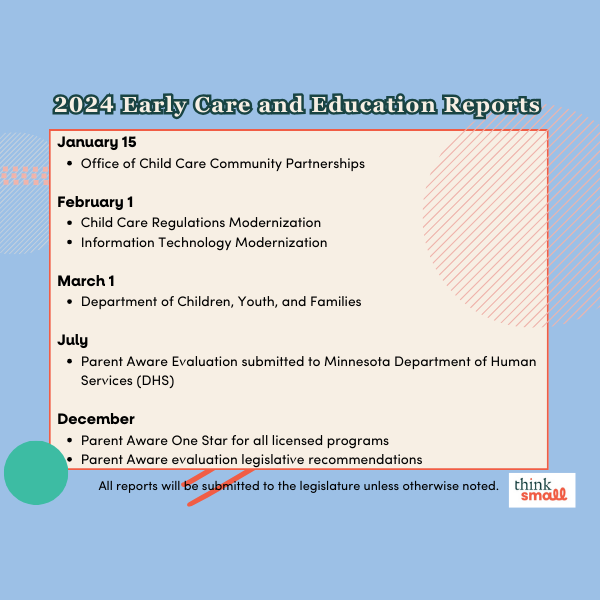

Refer to our previous blog post on Minnesota’s early care and education landscape for additional historical context.

After all that’s transpired in the past 40 years in programs, policies, financing, and society, it is no wonder that early childhood systems struggle to coordinate efforts, demonstrate results and provide uniform measures.

Thanks to the hard work of Jody Hauer and her team at the Office of the Legislative Auditor (OLA), we now have a current overview of how these programs function. The OLA recommends improvements in how systems operate—streamlining, identifying, assessing, collecting and sharing data. Accountability is a good thing and frustration is understandable. There are no standardized data. Nothing is comparable. Systems exist at multiple levels of government.

Elders see.

There are many promising developments in the works.

Elders worry.

Data collection systems are expensive to develop, especially in complex multi-level systems.

Elders wonder.

Given the paucity of investments in families and program and systems that serve them, how much of these scarce financial and human resources should be spent on data collection systems? What proportion should be spent on direct supports for families?

One approach to answering these questionsis to ask a broad audience that includes engaged families and communities. What are the three outcomes that are most important for young children and their families? An answer to this question could suggest a base of common information to gather across governing agencies.

Elders caution.

A MARSS number is not accepted by Medicaid; child outcomes are very difficult to measure unless you’re a researcher; kindergarten readiness includes a large “window” of children whose age ranges can span a year or more at the point of kindergarten entry. The safety net that undergirds early childhood programming is frayed.

Elders recommend:

- Evaluations should aim first to improve programs, not judge effectiveness

- Invest in capacity of workforce to integrate new science of child development

- Increase resources that support families and their ability to parent their children

- Develop outcomes that engage families, embrace culture, and incorporate new science of development (including impact of trauma on learning and health across the lifespan)

Concluding Thoughts

The field of early childhood encompasses multiple disciplines, a range of professions, a blend of community practices, cultural knowledge and values. One size will not fit all. The importance of “prenatal to three”—beginning before birth—is supported by a growing body of research. Development at this stage of life is holistic, rapid, and wholly dependent on relationships and experiences provided by caring adults—more than at any other period of across the lifespan of human development.

There is no “system” in place that supports this development. Early care and education is a case in point. Living wages and benefits for early care and education staff are essential for the provision of quality care. However, Minnesota lags behind many other states in delivering a commitment to workforce development and compensation. Turnover among child care staff is significant, and is due primarily to low pay. Our children grieve these lost relationships on a daily basis.

There also is no such thing as just a “baby”. It is always “a baby AND a parent or close caregiver” developing in the context of relationships. Supporting both the baby and the adult is essential. In highly stressed environments, parents and other caregivers require help in buffering the extreme stress experienced by their young children. Providing high quality child care is one strategy to support parents and babies, but it’s not a silver bullet. Holding early care and education programs to outcomes for which they have only partial influence is a recipe for discouragement.

In fact, there is much we can accomplish IF we commit to working differently together, commit to learning, to be willing to be uncomfortable—to resist defensiveness.

We cannot change the reality of competing programs, conflicting policies, confusing funding streams—certainly not overnight. We have available policy and administrative vehicles that can achieve many of the recommendations set forth in the OLA report—especially with an applied developmental lens. In fact, there is much we can accomplish IF we commit to working differently together, commit to learning, to be willing to be uncomfortable—to resist defensiveness. It requires re-thinking our assumptions about families and children, beginning before birth, applying a new lens to our approach to working with families, and re-tooling the current and future workforce.